- Home

- Don Wilding

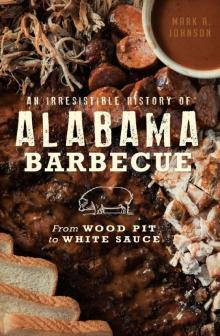

An Irresistible History of Alabama Barbecue

An Irresistible History of Alabama Barbecue Read online

Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright © 2017 by Mark A. Johnson

All rights reserved

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.43966.212.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017938334

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.702.7

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

I dedicate this book to my wife, Kate, who introduced me to Alabama white sauce and supported me in the publication of this book.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. “A Delicious Flavor in No Other Manner Obtainable”: The Origins of Alabama Barbecue, 1492–1800

2. “Freedom Which Knew No Restraint”: The Madison County Anti-Barbecue Reform Movement, 1820–1840

3. Old-Fashioned Barbecue: Alabama Barbecue in the Eras of the Civil War, Reconstruction and Redemption, 1850–1890

4. Dirt Floors and Roadside Shacks: The Origins of Alabama Barbecue Restaurants, 1890s–1930s

5. Dreams and Opportunities: Black Barbecue Entrepreneurs in the Civil Rights Era, 1940–1970

6. Hog Heaven: The Proliferation of Alabama Barbecue Restaurants, 1950–1980

7. Barbecue and Beyond: Alabama Barbecue Restaurants in the Twenty-First Century

Conclusion. A Blast from the Past: Alabama Barbecue Clubs

Notes

Bibliography

About the Author

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am thankful for numerous people who have helped me with this book. I am particularly grateful to the Southern Foodways Alliance, especially John T. Edge, and the Alabama Tourism Department. They provided me the opportunity to study Alabama barbecue. I could not have done this project without the oral histories conducted and archived by the Southern Foodways Alliance.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Joshua Rothman. With the grant funded by the Southern Foodways Alliance, he hired me to produce the now-entitled essay “Pork Ribs and Politics: The Origins of Alabama Barbecue.” I would never have approached barbecue from a historical perspective if not for his choosing me. I could never have completed the project without his assistance and encouragement. In the process of writing the article, I received help from many people, especially at the University of Alabama, including Dana Alsen and Megan Bever.

In the process of turning the original article into a book-length project, I encountered many helpful people and their scholarship. I benefited from the work of many scholars, especially Angela Cooley, who helped me take my first steps into food history. I owe much of my initial understanding of the subject of barbecue to the work of historians Robert F. Moss and Valerie Pope Burnes. In my own work, I have attempted to live up to the standards set by these scholars. I have blended their work with my own research to trace major historical developments with specific attention to Alabama’s unique people and places.

During the research phase of producing this book, I accumulated many debts. I would like to thank the many restaurateurs who spent time sharing their stories and feeding me. I hope I have done justice to your hard work. I would also like to thank the staff at the Center for the Study of the Black Belt at the University of West Alabama. They helped me find archival material related to this project.

Finally, I am grateful to the support of family and friends. First, I would like to thank my parents, who taught me to love history and how to work hard. Next, I would like to thank Pat and Melissa, who gave me the nickname “Dr. BBQ.” I could not have completed this project without the love and support of my wife, Kate, to whom I dedicate this book.

INTRODUCTION

Alabama barbecue serves as a source of state pride. Nationally, Memphis, North Carolina, St. Louis and Texas get the publicity. In restaurants and backyards across the state, Alabamians boast about the state’s barbecue. They have put their own barbecue up against the food from any of these other places. In these contests, they have had their fair share of victories.

Within the state, however, Alabamians do not even agree about how to define Alabama barbecue. In the Tennessee River Valley, barbecue means chicken with white sauce. In Birmingham, barbecue entails pork on a sandwich with a tomato-based sauce and a couple pickles. In Tuscaloosa, barbecue consists of ribs basted with a spicy vinegar-based sauce. These generalizations still do not adequately describe Alabama barbecue. In the Tennessee River Valley, for example, customers can also find mustard-based hotslaw at many of the local restaurants, especially in the Shoals.

If barbecue does not have a defining ingredient or flavor profile, it does have a unique story. In Alabama, barbecue transcends race, class and generational boundaries and relies on a multi-racial and multi-ethnic restaurant-based scene emphasizing open pits and hickory wood.

From the beginning, Alabama barbecue did not necessarily have these characteristics. Instead, they developed over time. These defining elements of Alabama barbecue have evolved over the past four hundred years, with roots in the Columbian Exchange, slavery and emancipation, Jim Crow and civil rights and the rise of the restaurant industry. In each phase of development, Alabama barbecue attained some of its present-day characteristics. This is the story I tell in this book.

Throughout the book, I weave many stories together. On the national level, historic events shaped how people produced and consumed food, including barbecue. In Barbecue: The History of an American Institution, historian Robert F. Moss explains these developments and their affect on barbecue across the nation. I could not have produced this history of Alabama barbecue without Moss’s path-breaking work. In this book, I have told a story about how national and local events played out in Alabama, affected the restaurant industry and, therefore, influenced barbecue in the state.

In this book, I refer to barbecue as a food, a cooking technique and a social event. As a food, Alabama barbecue consists of many different types of meat, sauces and preparation methods. I have used the term to describe all of them.

Finally, I want to emphasize that people from numerous ethnic and racial groups made their own contributions to Alabama barbecue. In fact, present-day barbecue could not exist without the blending of techniques, recipes, ingredients and labor from Native Americans, Africans and Europeans. So the story of Alabama barbecue begins at the point of contact between these groups of people, long before Alabama, as an entity, even existed.

CHAPTER 1

“A DELICIOUS FLAVOR IN NO OTHER MANNER OBTAINABLE”

The Origins of Alabama Barbecue, 1492–1800

In the 1000s, the Norse Vikings colonized northern North America, in present-day Newfoundland. Although their settlement of L’Anse aux Meadows did not last long, Vikings continued to visit the area to fish and hunt whales. Frequently, they came ashore to process their catch but also to trade with Native Americans. In 1492, Christopher Columbus and his crew arrived in the Caribbean. In 1493, Columbus returned with a massive fleet to commence the Spanish colonization of the Caribbean.

When Europeans made landfall in the Americas, they brought with them people, plants and diseases previously unknown to the Nati

ve Americans. Likewise, the Europeans discovered things native to the Americas that Europeans had never known. Europeans and Native Americans coveted one another’s strange things, so they traded. This process, called the Columbian Exchange, forever changed the world.

The Columbian Exchange revolutionized cuisine around the world. Before the Columbian Exchange, Italians did not have tomatoes. The Irish did not have potatoes. Europeans brought these items, and many more, back with them from the Americas. Similarly, Native Americans did not have beef or pork until Europeans brought them. Native Americans did not have coffee either. They also did not have wheat or rice. Native Americans had chocolate, but Europeans had sugar. Without the Columbian Exchange, therefore, the modern chocolate bar could not exist. The Columbian Exchange made modern-day cuisine possible, especially barbecue.

Barbecue has its origins in the first encounters between Europeans, Native Americans and Africans. Out of the interactions between different cultures, colonial Americans developed the cooking method, food and social function known as barbecue, which became a staple of social and political life in the English colonies.

As the descendants of these colonists migrated to the Deep South, they took their customs with them. Through the processes of cultural interaction and migration, barbecue arrived in Alabama, where it became entangled in questions of power, status and freedom. The story of Alabama barbecue, therefore, begins in the first moments of contact between previously unknown peoples.

BARBECUE AND THE COLUMBIAN EXCHANGE

Native Americans, Europeans and Africans each contributed to the development of the cooking technique, food and social event that became barbecue. Native Americans provided the method. Europeans contributed new meats and new sauces. Enslaved Africans provided the labor, which means they had significant influence over the perfection of the recipes and techniques.

On Columbus’s first voyage in 1492, he and his crew encountered the Taíno people in present-day Cuba, where they learned about barbecue. Near Guantanamo Bay, Columbus’s crew witnessed these indigenous people cooking hundreds of pounds of fish over the indirect heat of embers. After the cooking had finished, the entire community gathered, seemingly without regard for social status or wealth, for the feast. Europeans observed a similar cooking method and social ritual throughout the Caribbean.1

When Europeans arrived on the eastern seaboard of North America, they observed local Native Americans barbecuing meat in a similar manner as the Taíno people of Cuba. In 1588, English explorer Richard Grenville and his crew met indigenous people in present-day North Carolina. On this expedition, John White served as Grenville’s official cartographer. In addition to his mapmaking duties, White also depicted the lives of the indigenous people in a series of watercolor paintings. In Europe, artists took White’s paintings and reproduced them with their own additions. In one of these images, Native Americans cook fish on a wooden framework over a fire.2

In 1588, Richard Grenville journeyed to the East Coast of North America. Here, his official cartographer, John White, observed Native Americans grilling fish on a wooden frame over a hot fire. He preserved his observations in a watercolor painting. When Theodor de Bry engraved White’s image, he added two semi-nude indigenous men. Library of Congress.

Europeans came to understand Native Americans through these images, which often contained equal parts truth and fiction. Despite never observing native people, engraver Theodor de Bry, who produced many images of the Americas, embellished White’s original watercolor with images of cannibalism. With these artistic additions, de Bry and other European artists mythologized the savage nature of the Americas and its people. Among Europeans, barbecue became associated with barbarism. Strangely, barbecue’s barbarism added to its appeal because European society had a rigid moral code. For many Europeans, barbecue provided an outlet for repressed desires.3

In travel journals, Europeans commented on this newly discovered cooking method, which required a wooden framework, low fire and extended cooking time. According to a European observer, the indigenous people “broil their fish over a soft fire on a wooden frame made like a Gridiron.” On a framework of green wood, or barbacoa, the natives kept the food about two feet above the embers to avoid burning. Under the framework, they built “so small a fire” that “it requires a whole day to make ready their fish as they would have it.”4 To European observers, this cooking method would have seemed strange yet familiar.

Based on John White’s watercolor painting of fish, engraver Theodor de Bry, who never observed the native people of North America, produced this image of Native Americans barbecuing human body parts. Library of Congress.

Before contact with Native Americans, Europeans did not barbecue meat but instead roasted and smoked it. In Europe, wealthy people roasted meat, but only for special occasions because it required special equipment and constant attention. Unlike roasting, the indigenous barbecue utilized indirect heat and gathered people from across the socioeconomic spectrum. In addition to roasting, Europeans had a long history of smoking meat. By smoking meat, they preserved it long after the slaughter and utilized every piece of the animal. Unlike smoking as Europeans understood it, the indigenous people’s barbecue took place outside in open air, not in a smokehouse. To the Europeans, therefore, the Native Americans demonstrated to them an entirely new cooking method and social ritual, even if it somewhat reminded them of home.5

For Columbus’s predominately Spanish crew, the sight of the barbecue might have reminded them of the txarriboda because of its festival-like qualities. Every year, Basque farmers revel in the txarriboda, an ancient tradition that celebrates the slaughter of hogs. Throughout the day of the feast, people prepare the smoked sausages and hams for the winter. After the work of slaughtering and preparing the meat, they enjoy a massive feast, dancing and singing. Although Europeans had encountered something new in these foreign lands, they had a reference point to understand it, and they embraced the new form of cooking.6

When Europeans adopted barbecue, they contributed new meats and new techniques. Although they witnessed Native Americans using the technique to prepare fish, game animals and, apparently, reptiles, Europeans used their newly acquired barbecue skills to prepare their own animals. Unlike Native Americans, Europeans had domesticated livestock, such as cows, goats, sheep and pigs, among others. Europeans barbecued all of them.

Among the many animals Europeans brought to the Americas, pigs thrived in the wilderness. In 1493, Columbus carried eight pigs with him on his second voyage to Hispaniola. In 1539, Hernando de Soto took some of the descendants of these pigs to North America, where they quickly spread across the continent. They are the ancestors of the wild pigs, including the Arkansas razorbacks, common in the Southeast today. In 1540, Hernando de Soto and his expeditioners encountered the Chickasaw tribe near present-day Tupelo, Mississippi. To forge an alliance with the Chickasaw, de Soto flattered the native people with massive feasts. Before refrigeration, people only barbecued meats to feed crowds large enough to consume the entire animal. The Spaniards, therefore, chose to barbecue pigs in honor of the Chickasaw chiefs, who would never have eaten pork before this encounter. In return, the Chickasaw chiefs presented food and clothes to the European travelers. Although this particular alliance between the Spanish and the Chickasaw did not last, barbecue had brought these people together.

In 1607, the English brought pigs with them to Virginia, where they outpaced other livestock in the colonies. Pigs reproduced quickly, did not require much attention from busy farmers and yielded large amounts of meat. These qualities made them ideal for the colonists. The pigs foraged for food in the wilderness. Unlike contemporary pork raised on commercial farms, these pigs would have been much leaner and tougher, which made them ideal subjects for the tenderizing forces of low heat in the barbecue pit. In journals and account books, Virginians counted many more pigs than other animals, if they even bothered to count them at all. When colonial Americans barbecued meat, it was likely por

k, but it could have been any of the other animals that local farmers happened to have on hand. 7

Europeans also contributed sauces. In travel accounts of indigenous barbecues, Europeans do not mention basting or sauces. In Europe, people basted their roasts with a variety of sauces. In France and Germany, people preferred to use mustard-based sauces. In England, people developed tart sauces out of vinegar. According to one medieval recipe, Europeans roasted birds with a sauce consisting of mustard and vinegar seasoned with powdered ginger and salt. In another recipe, author Thomas Dawson recommends basting meat with a sauce of vinegar, ginger and sugar.8 These sauces bear resemblance to modern-day barbecue sauces, like the mustard-based sauces in South Carolina and the vinegar-based sauces of North Carolina. When Europeans came to the western hemisphere, they introduced basting and sauces to barbecue to help keep the meat moist as it cooked.

When barbecue took hold in North America, enslaved Africans barbecued food for white families and white events but also for themselves. At most barbecues, enslaved people smoked meat on poles situated over long, earthen trenches that glowed with hot coals. When enslaved Africans held their own barbecues on holidays, white masters often donated meat, such as pork but also beef, mutton and other meats, for the event. Enslaved people smoked the meat and served it alongside food gleaned from Native American recipes, such as cobbler, sweet potato pies and corn bread, as well as European treats, such as cakes, pies and custards.9 Through the process of cultural exchange, the modern-day southern institution of barbecue was born. Even in the food’s infancy, barbecue as a cooking method and a social ritual consisted of many of the elements that would eventually define the food in Alabama.

BARBECUE AND POWER IN EARLY AMERICA

In the seventeenth century, colonial Virginians made barbecue a staple of their events held on behalf of community development and politics. In 1607, English settlers arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, where they barbecued meat because of its similarity to the traditions of their homeland. For the most part, the settlers of colonial Virginia came from southern and western England. In these parts of England, people tended to roast and broil their meat. They also had a vigorous festival culture, which colonists replicated in their new homes.10

An Irresistible History of Alabama Barbecue

An Irresistible History of Alabama Barbecue